The following post is a long and detailed account of my experience researching the Indian film industry on my first trip to India in May 2012. It was a 15-page article I was hoping to get published somewhere, but since I have this blog now I can just post it here. I originally wanted to post it in sections but decided that since it makes sense chronologically it wouldn’t be a good idea to split it up. It has been organized by location, starting with Vancouver, then Chennai, Mumbai, Pune, Hyderabad, then Chennai again before the conclusion. Read on if you are curious about the Indian film industry, and our experience learning about it.

Click here to read a shorter version with references to the current state of the BC Film industry.

“Mounties in Mumbai”

Two Students’ Discovery of the Indian Film Industry, and Where Canadian Coproduction Potentials Lie

On a cold February day, I checked my email and saw a message with the subject “Internships in India this coming summer”. Excited, I opened it up to find that the project was with a 3D animation company, but unfortunately required that the student have animation experience. Having no experience myself, I gave up hope and India became a distant dream once again.

Two months later, I had a change of heart. I dug up the old email, and asked if the position was still available. Patricia Gruben, the head of Praxis Center for Screenwriters and SFU professor, replied and let me know that she would take my C.V. but that the interviews were starting the next day. Patricia was not actually involved in the internship program but was asked to find candidates because of her experience in India as well as her involvement with the film department. I came to the interview, stated my travel experience and what I did in the film program, and got one of the two positions available. I have focused on writing, directing, and sound design, and my classmate Sara Blake, who also applied and got the job, specializes in writing and cinematography.

As it turned out, the 3D animation gig had fallen through. At this point Patricia was trying to set up an internship for us in Chennai at IIT Madras with Aysha Iqbal, a film appreciation professor organizing a summer workshop. Other than this neither Patricia, Sara nor I had any idea what we were going to do in India for the rest of the summer. An appointment was made for us to meet the mastermind of the SFU Initiative program, Navinder Chima, and find out what on earth the program was and what was going to happen.

In a nutshell, the SFU India Initiative is a program with the goal of increasing collaboration between Canada and India. With generous support from Western Economic Diversification Canada, SFU sends students to India to be immersed in the industry that corresponds with their studies. Focusing on mobility programs and projects that support the clean energy, life sciences, new media and film sectors, they are given money for expenses ranging from plane tickets to food, and they typically intern with an Indian company for a minimum of 6 weeks. On their return to SFU they deliver a report of their findings. The ideal result is increased and tighter linkages with India, and a great experience for the students. There was only one hiccup.

The problem was that there was no formal internship setup for us. The Imaging Cinema workshop with Aysha Iqbal was only 10 days long. So what were we going to do with the rest of our time? Sara and I put our heads together and we decided to create some goals for ourselves. We both wanted to travel around India and not be stuck in one city for the whole trip. We wanted to find out what filmmaking was like in India, and what Canadian filmmakers would expect while working there. What could these two countries offer each other? What kind of exchanges and partnerships could we try setting up with SFU and Indian film schools? I would also be lying if I said I was a fan of Bollywood cinema before the internship. We both had very little exposure to Indian film, and wanted to know more about the magic of the song and dance that captured an audience of billions of people worldwide. Little did we know Bollywood isn’t the only kind of cinema being produced in India.

So how were we going to find out all of this? We tried Google and Wikipedia, believe me! This is what we decided: We would go to India for 10 weeks. We found out that there was also a Kollywood (Tamil cinema based out of Chennai), and a Tollywood (Telugu cinema based out of Hyderabad) so we would spend 3 weeks in Chennai, 4 weeks in Mumbai, and 3 weeks in Hyderabad. Before going we would meet lots of Vancouver filmmakers and producers who had worked on projects in India and ask them about their experience. Once we got to Chennai, we would use the workshop as a starting point for gathering contacts and see how far we could get by talking to the speakers and participants. If networking failed, then we would try to visit studios and film schools in the different cities. And if all else failed, we would enjoy our time in India as tourists.

The following pages are a chronological description of Sara and my discoveries and the people we met along the way. The conclusion is a brief summation of what we learned about Indian cinema, but how we reached these conclusions is the most interesting part. Please keep in mind that this is a non-academic article and the theories and opinions stated are not necessarily absolute fact but interpretations of our observations and interviews with people working within the industry.

Vancouver, British Columbia: Treaties and Documentaries

Our biggest priority was to have an idea of what is currently being done in India, and find out where Canadian interests lie. However, first we needed a refresher course in coproduction. As this article is intended for public readership of all levels of knowledge and experience, I will go over the basics of coproduction treaties and why Canada needs them.

Jack Silberman, film and television producer and writer of “Call it Karma” had a good chat with us and discussed the basics of coproduction. In order for a film to be considered Canadian and sell its distribution rights, it must qualify by having enough CRTC points. These points are awarded based on the nationality of the filmmakers. Points are given for Directors, Cinematographer, Producers, Actors etc. and certain roles get more points than others. If the film has enough points, it qualifies as Canadian and can be pre-licensed allowing for the selling of distribution rights and thus the film gets funded.

A coproduction treaty allows for some of the point-giving roles to be filled by crew of the corresponding country. It also allows funding to come from both countries although there must be Canadian producers. There are also certain safety nets that are put in place to prevent labor imbalances and clauses that protect the interests of both negotiating parties.

Brigitte Monneau of Telefilm Canada filled us in on the current state of the Coproduction Treaty negotiations with India. Treaty negotiations began about ten years ago, but were halted and not resumed until September 2011. Treaties typically take 2-4 years to negotiate, and another 18 months to implement after they are signed. However, negotiations with India have been difficult in the past because the Indian industry is privately run and regulated. Now the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting has been brought in to act as the negotiating representative for the Indian film industry, but it remains to be signed.

However, just because there is no treaty signed between India and Canada, Canadian filmmakers haven’t been stopped producing film in India. There have been many films shot in India including Vic Sarin’s “Partition” which had some sequences filmed in India although mostly made in sets within Canada. Also, documentarians such as Nimisha Mukerji (65_Red Roses), and Meghna Haldar (Dirt) have gone into India and shot under the radar with local crews. Nimisha went to India to shoot for her upcoming film “Blood Relative” and brought only her cinematographer. She hired a local sound recorder and other crew and brought back the footage to Canada and finished the film within the CRTC points system.

So what was production like in a country like India for these documentarians? We learned through talking to Nimisha, Jack, and Jayanti Ram (CNN) that documentary is not a common form of filmmaking in India and it is difficult to work with Indian crews who have no experience in the medium. There are some Indian crews that specialize in working with foreign documentary and news crews. There are some crews who have been trained by companies like the BBC and continue to work with foreign productions. However documentary is a largely unpracticed form of storytelling in India. In fact, the NFDC produced a bunch of mini-documentaries that play as a pre-show before theatrical films, but the style of documentary is more like a public service advertisement. As a result, this is what many Indian audiences consider to be documentary. Also, a commonality between all documentary filmmakers’ experiences is that they found it absolutely necessary to have a designated ‘Fixer’ on set. A Fixer is an Indian crewmember whose sole job is to fix the problems that crop up for foreign crews including trouble with police, bribes, and translation. They are essential to a production manager because there are many differences in the way films get made in India.

Luckily, India has the common language of English despite its cultural and linguistic diversity. With the world trying to decide whether or not to invest in China or India, film coproductions will definitely be easier with India because they are already working in the same language as Anglophone Canadians.

Chennai, Tamil Nadu: Introduction to India, Its Filmmakers and Film Students

Not knowing what to expect, Sara and I suddenly found ourselves in the Chennai mid-summer heat. We stayed on the campus of IIT Madras thanks to the organization and hospitality of Dr. Aysha Iqbal, film appreciation professor at IIT Madras and Curator of the Imaging Cinema workshop. Unable to be of much help in comparison to Aysha’s many student organizers, Sara and I sat in the lectures and went through film school boot camp. The Imaging Cinema workshop has been a screenwriting workshop for the last three years, but this year it was expanded into a film-appreciation course and the students finished the 10-day workshop by writing, shooting, and editing 3-minute films in groups with a screening on the final day.

Monkeys on campus at IIT Madras

The days consisted of lectures from industry professionals, panel discussions with filmmakers, and private film screenings at night. We had the opportunity to interview Sriram Raghavan (Agent Vinod) and Shridar Raghavan (Dum Maaro Dum) and Ravi K. Chandran (Cinematographer of Saawariya) on their work and their take on the Indian film industry. We also got to have a great discussion with Sudish Kamath (“Goodnight, Good Morning” and film critic for The Hindu) and Atul Tiwari (Screenwriter) on what separates Indian cinema from all the rest.

If you have watched a few classic Indian films, you may have realized that they are almost always have a 150-minute run-time. One of the contributing factors is that all classic Indian films are meant to be epics. Because of language barriers, the Indian audience that watches these films is narrowed and the films have to cater to a larger audience demographic. Each film attempts to cater to the full range of emotions and encompass all genres including slapstick comedy, to romance, to action, and suspense. This is done with the hope that every audience member can have a favorite moment in the film. Another large part of why this is a difficult form for filmmakers to break free of is that this is has become a type of requirement for the general mass-audience. The cinemagoers that bring the most views come from the towns and villages instead of the urban centers. The reasons for this can be speculated on, but it is true that audiences in rural India will often see a movie in the theatre more than once. A North American parallel to this experience could be the way that many people will go see their favorite band more than once. So if a film wants to be marketable to these audiences it must be the full production value they are used to or it is considered a waste of their money and think they are getting ripped off.

Of course, this isn’t true of all Indian audiences. Urban audiences tend to be more exposed to international cinema because the cities have multi-screen theatres that can find space for the latest James Cameron film. These audiences also tend to be more educated than the rural audiences, and that is reflected in the ticketing price. Multiplex theatre ticket prices typically sell for between 200-350 Indian Rupees (4-7 dollars) per head, while single-screen cinemas only charge 55 rupees (1 dollar). Typically, the most successful films regain most of their money in rural areas, which means that they cater to audiences that expect the full 150-minute experience. While there is a new wave of Indian cinema emerging, these films have not yet been able to reach the same level of commercial success.

There are other distinguishing factors like song and dance sequences and intervals. Because music is so key in the marketing of a film, commercial films will always have songs. While watching these huge epics, songs are not only used as a way of telling the story but have also been used as an emotional break or transition between scenes. While music provides an emotional relief, sitting at the theatre for 150 minutes can also take its toll on your body. The films will often have an Interval of about 10 minutes for the audience to have some physical relief, stand up and stretch or use the bathroom.

One thing that was crystallized in our understanding of Indian cinema during the time at the workshop is that Indian cinema is so much more than Bollywood. In our interview with Ravi K. Chandran, he eloquently put that Indian cinema is like Indian cuisine; each region has its own flavor, its own dish, and its own language. While the form is similar and recognizable, the content varies. Currently, every region of India has its own cinema however small the industry. The ones we had time to research were limited to the cities we visited, namely: Mumbai, Pune, Hyderabad, and Chennai.

Bollywood is based in Mumbai and the films are Hindi-language. The name Bollywood is derived from the city’s old name, Bombay. While Bollywood is the dominant industry in Mumbai and India, Hindi and Marathi-language films are also being produced in the city that don’t prescribe to the classic Bollywood commercial cinema so loved by ‘the masses’. In the past, anything that wasn’t Bollywood was considered to be Parallel cinema. Now there is a New-Wave movement emerging from Mumbai and other parts of India where filmmakers are producing independent cinema that challenges the accepted formula of Bollywood. In fact, the movement is becoming so popular in India that New-Wave films are having some commercial success and mainstream studios and distributors are starting to take on directors such as Anurag Kashyap whose most recent films “Gangs of Wasseypur 1&2” are now being represented by Viacom.

The neighboring industry to Bollywood is based in Pune. It is considered a regional cinema because the language is Marathi, the main language of the state of Maharashtra that encompasses both Mumbai and Pune. Within Pune is the most famous film school in India, FTII (Film and Television Institute of India) located in an old studio complex. The Marathi-language industry is not so prolific as the Hindi-language industry because less people speak Marathi, and Bollywood overshadows it. I would compare the relationship to that between Hollywood and the Canadian film industry except the languages spoken are different. The Marathi film industry produces many films, but unfortunately only very few make it to the distribution stage. This is something I will elaborate on later.

Hyderabad has a booming industry that produces about 200-300 films a year. The commercial film industry in Hyderabad is called Tollywood because the language is Telugu. The industry is amazing because it produces so many films, but the audience that consumes the cinema is limited almost entirely to the state of Andhra Pradesh. While Telugu audiences may speak some Hindi, it is not common that Hindi audiences will also speak Telugu. This is why Tollywood is limited in its non-diaspora audiences, just like the Marathi industry. The sustainability of an industry like this is reliant completely on language. Partially because of illiteracy, it is extremely rare to find a film projected in India with subtitles. Another reason is India’s remake industry. It is a common practice to take a film that is successful in one language, and remake it in another with a few story changes in order to make it immediately more relatable to the respective audience. A recent Telugu box-office hit was the film “Gabbar Singh.” The rights to remake the film in Hindi were bought as soon as it became clear that the film was making money.

Let us not forget the booming industry in the Southern city we were visiting, Chennai. The films are in the Tamil-language and the industry is called Kollywood. The name originated from the film-district Kodambakkam where there is a concentration of studios including the most well known, L.V. Prasad Studios. This industry also produces 200 films a year and is run on a similar language-based distribution model as Tollywood. During a discussion on the differences between Northern and Southern Indian cinema with the Raghavans and Thiagarajan Kumararaja (Aaranya Kaandam) at the workshop, it was noted that Tamil cinema tends to make more generally-appealing stories because the language group is smaller so they need to make it family-friendly to expand their viewership as much as possible. In contrast, Hindi-language cinema has a broader audience and as a result they have a bit more freedom to make films for niche markets.

While we visited Chennai, we had the chance to visit L. V. Prasad Film and Television Academy which is located inside the Studio complex and Directed by Mr. K. Hariharan. Because of the film school’s location, they are at an advantage over Vancouver-based film schools because they have immediate access to professional studio facilities. Uma Vangal gave us a tour, and since this was the first film school that Sara and I visited, we were blown away by the sets and studio space the students could use. On the other hand, the digital technology available to the students is not top-of-the-line. The editing room is a shared cluster of PC computers with dividers separating the filmmakers. The sound editing and recording rooms are also small and under-equipped in comparison to the facilities at other schools. On the plus side, the students get to do the final mix of their films in the same mixing rooms as the professional productions. There is also the benefit of being in close-proximity to the working industry and having the opportunity to interact with professionals every day. Despite the school’s technical setbacks, the class sizes are quite small and that enables the students to have much more hands-on practice. The school was founded in 2005 and offers diplomas in Direction, Cinematography, Editing, and Sound Design with a syllabus that is hands-on and project-heavy.

Editing rooms at LVP Film Academy

We wrapped up our stay in Chennai with a quick trip over to Pondicherry to recover from the intense workshop. We were very excited to move onto the next stage of our journey, Mumbai, to meet again with the people we made connections with in Chennai and expand our research by gaining new perspectives on Indian cinema in a less-formal environment.

Mumbai, Maharashtra: Learning How to Make a Film Over Coffee

After a 24-hour train ride across the country, Sara and I landed in Mumbai. The moment we had a working mobile phone, we informed everyone of our arrival. Not even an hour went by and we had a message from Ravi K. Chandran inviting us out to Film City for a commercial shoot. We dropped our bags off at our hostel in Colaba, and took the one-hour train ride to Goregaon and the famed Film City.

Film City is an integrated film studio complex on the edge of Sanjay Gandhi National Park. It was built by the state government in order to support the film industry, and spans an area of many acres and is a great area to drive around. There are mansions, apartment buildings, and villages ready to shoot in. There are also many studio spaces for indoor shooting. We got through the security gates and showed up at one of these indoor studios just in time for lunch. It was a shoot for Fair and Lovely whitening face cream. We got to watch the production, and everything proceeded in the same way one might expect a commercial shoot to function in North America.

The only noticeable difference we saw was when we crossed over to a shoot in the studio next-door and found a feature-film shoot. There were over one hundred crew on set, but about half of them were standing around drinking chai while the rest were shooting inside a train carriage. Ravi K explained that when an Indian production rents equipment, each piece of equipment comes with an operator. This means that a camera unit could consist of a minimum of five people, and every light comes with a grip. This may seem inefficient, as anyone who has worked on a small film crew will know that a camera only needs one person to operate it, and perhaps a few people to handle all the lighting equipment. However, unemployment is a large issue in India and the total combined salary of the camera unit per day would still be less than what a camera operator would make in North America. Ravi K. Chandran admits that while it is not necessary, people get paid and the film gets made.

We went back to the commercial shoot where shooting was proceeding as planned. It started to rain and the sound was deafening. Normally this would put a production on hold but the shoot continued on as if nothing had changed. The studios are fairly old, and shooting with synchronous sound was rarely done until recently. As a result, most Bollywood productions are shot with a guide track and then dubbed over regardless in order to achieve a consistent sound throughout the film. Having made films in this way since sound was first used, India has a large pool of very talented voice-actors who specialize in dubbing. In fact, it wasn’t uncommon for actors to just mouth gibberish if they didn’t know the language or the script and have it dubbed over by another actor.

Another Indian film school is Whistling Woods International Institute (WWII), which was founded in 2005 and built within Film City. Currently there is a dispute over the land it was built on, but the original deal exchanged the land at a low price while giving Film City a 15% share of the school. Despite political issues, this school stands above all others in India. We received a special tour and were blown away by the technical facilities of the school. Not only did it have a large theatre for exhibition, the latest editing technology on Macintosh computers, and a beautiful sound recording studio and mixing stage, but the students also had the opportunity to learn how to use 3D cameras during their education. While the school does not allow the students to shoot their thesis films on 3D, they have a chance to do group exercises where they learn the workflow of the medium. The head of the screenwriting department is Anjum Rajabali, a noted screenwriter who has also worked with Praxis Centre for Screenwriters. Anjum and the head of WWII business department, Chaitanya Chinchlikar, sat down with Sara and I and not only gave us some insight on the film industry, but also gave us an invaluable list of contacts and references to help us in our research in Mumbai, Pune, and Hyderabad.

Another pair of individuals who were more than helpful when it came to expanding our contact list was Shridar and Sriram Raghavan with whom we had interview in Chennai. They also invited over Rohan Sippy who was speaking at the workshop in Chennai but we never had a chance to meet. After a meeting in their office, we had more contacts than we could meet. We refocused our research and booked meetings focusing on the cinematography and production side of filmmaking in India.

Hanging out on a shoot

The first of these meetings was with Deepti Gupta and Manoj Lobo, both cinematographers in different sectors of the industry. Deepti specializes in independent films and documentaries, and Manoj started in the commercial sector of film and is now a cinematographer on many Bollywood films. From them we learned something very important. Despite our experience on set with Ravi K. Chandran, traditionally Indian film production runs on a more ‘feudal system’ on set. By feudal, it is meant that the entire crew is at the whim of the director and technical skills are valued more than managerial. A role such as Assistant Director would previously have no recognition on set because the skill set required no technical training and it was considered the job could be done by anyone. As a result, a person who works what is considered to be one of the most important jobs on set in North America would get paid a fraction of what a camera operator would make. This is how production worked in India for quite some time. The process is chaotic, and the director has absolute power over the producers. This style of working is still common in India, particularly in the South where corporate production companies have no yet gained a foothold. However, the Western set hierarchy is also common practice, and I think it would be a mistake to say that it is the wrong way of doing things. Perhaps the feudal system is not as efficient as the Western model, but in the end the film gets made. This is something that could require adjustment for a foreign filmmaker coming to India for a coproduction. Nevertheless, it is important to be flexible and understand that the film will still be completed. Resistance is futile, and the best way to emerge from a project would be to go with the flow and be prepared for a bit of chaos instead of fighting every step of the way.

Another very important thing for Sara and I to find out was the role of women within the Indian film industry. Up until this point we had only asked men about gender equality in the industry, and the men we had asked were screenwriters and directors with the exception of Ravi K. Chandran whose most recent camera assistants have both been women who have gone on to start their own careers in cinematography. The overall impression we had received up until this point was that the ratios were fairly equal to those seen in North America. There would be a split of roughly 30/70 women to men on set. However, Deepti pointed out that while there are women on set, they are almost always in assistant positions. It is rare to find a woman in India as the head of a department on set. There are only a handful of women Cinematographers in India, and only two of the last hundred films produced had female Directors. However, Sara and I did manage to meet some great female producers in our time in Mumbai.

The first producer was Purva Naresh, Executive Producer of Fiction Films at Reliance Entertainment. We wanted to know what sources of funding were available for filmmakers in India, and what were the current trends producers were looking for in the industry. Purva informed us that Reliance is one of the few production companies that is currently producing regional cinema. At that time, Reliance was producing predominantly Action films, although they had just completed production of their first animated film, “Krishna Aur Kans”. Typically, the trend in production shifts between Action genre films and Romantic Comedies every few years. Currently, Reliance has had its eyes on the South and are looking to integrate themselves more by either bringing southern filmmakers to Mumbai, or more ideally to produce films within the South. Sara and I also learned that the main contributing factor of a film being made or not depends almost solely on having a star signed up for the project. Typically, a filmmaker will approach a star with a script before a production company because if a star likes the film enough they will either produce it themselves or vouch for the film on behalf of the filmmaker. This is because the biggest selling point in commercial Indian cinema is the star quality. If there is a big star involved in the project, a big part of the marketing and sales has already been taken care of. However, not all successful Indian films manage to get stars but find other ways to be produced.

Historically, private studios have dominated Indian production. A well-known family-owned studio would be Banerji Productions. There has also been a bit of government funding available to first-time filmmakers provided by the NFDC and local state organizations. Recently, some of these government-funding programs have been reduced. There are also some programs such as the Children’s Film Society of India that gives funding to filmmakers who decide to make a film on children’s themes. Another viable option for production in the past has been private businessmen. It isn’t uncommon for a Non-Resident Indian to return and make a film. The issue with this method is that the films are often shelved after post-production and seldom make it to distribution. Outside these three, there have been two more recent forms of production that have been finding their way into the industry. The first is American-style corporate production houses such as Fox-Star Studios and Reliance Entertainment. The methods of production practiced in these studios is much more regulated that the “feudal system” of filmmaking. This has resulted in difficulty for these companies to find their niche in India at first. However, they are gaining a foothold in Northern India and Hindi cinema despite their continued difficulty breaking into the Southern industries. Another method is crowd funding. Although India presently has no crowd-funding platform such as Kickstarter or Indie Go-Go, Vasan Bala’s debut feature produced by Guneet Monga and AKFPL Productions was entirely funded through Facebook. The film was a great success and made it into TIFF 2012, cementing crowd funding as a viable production-option for those filmmakers who are up for the challenge. Coproduction has never come up in conversation with Indian filmmakers and producers as a way of funding a film. A way of increasing the chances of the coproduction treaty being signed between Canada and India is to increase the awareness of coproductions as a viable option for Indian filmmakers.

Caught on camera at Anurag’s office

After a bit of headhunting, Sara and I finally managed to track down Anurag Kashyap (Dev. D, Gangs of Wasseypur) whom we had met for a total of 10 seconds in Chennai due to the fan mob that surrounded him. He had given us his card and said to come by and visit the AKFPL office when we were in Mumbai. After that initial interaction we had to wheedle his personal mobile number from friends in order to confirm any sort of meeting. This sort of difficulty can be expected when trying to get an interview with one of the most influential contemporary directors in India. Anurag Kashyap has now directed over 10 films of his own, and has been writing and producing many others in his career. When we met him at his bungalow office-space, he had recently formed Phantom Productions in addition to AKFPL and both companies together were currently producing a total of 18 films in the year of 2012, inclusive of shorts and features. Anurag’s production space is more of a community center for independent filmmakers than a studio. Located in a two-story bungalow, the main hall and staircase is dedicated to a communal space for writing, discussion, and reading. There are also two editing suites, a VFX room, a multipurpose space for meetings and auditions, and a working kitchen for all to use. This space is where a great portion of India’s New-Wave cinema movement is emerging. Anurag does not finance the films himself, but acts as a creative producer guiding the filmmakers through the process. His partner Guneet Monga acts as Producer, keeps the filmmakers in-line, helps them access finances, and manages the logistics of the projects. Without this communal space for the filmmakers, many of the new-wave films found this year at Cannes and TIFF would never have happened. This is a new form of filmmaking that challenges the Bollywood norm, and yet is still managing to have some success in the industry. When asked if the production model was working, Anurag stated that it was too early to tell, but that he would continue to make films until forced to stop.

Our final meeting with a producer was with Swati Shetty. She had previously worked as Creative Producer for Disney International Productions and then President of Banerji. Only recently she has left both the corporate and the private studio modes of production and started the independent production company called Samosa Stories. When we had met, she was in the process of reading scripts. When asked what she was looking for, the biggest factor was the story. She was reading three screenplays a day and had not yet found anything worth pursuing. From our own experience with Indian film schools and the industry in general, it seems that screenwriting tends to be overlooked as the foundation of a film. Instead, the foundation of commercial films in India are the stars. When asked if she would be interested in doing coproductions with Canada, her answer was simple: If the story is right for a coproduction, then yes. India currently had coproduction treaties with Brazil, Germany, Italy, France, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom.

Right before we left Mumbai, we decided to take a serious look into the animation industry. This was something that none of the filmmaker’s we had talked had had much experience with. Luckily within Film City and associated with WWII is Maya Productions, a company that was founded by filmmaker Ketan Mehta in 1996. Ketan has already done a coproduction with France, and he explained that all a film needs to be a coproduction in India is government clearance of the script, and the censorship boards are not as conservative as they used to be so most applications go through without any changes. An offshoot of this company is Maya Digital Studios, where a good amount of animation work is being done. Founded only a few years ago, Maya Digital Studios has been building its own animation 3D Stereoscopic platform and is currently doing a variety of work in film, commercials, and games. Having just completed the 2D to 3D conversion of “Piranha Double D” this year, Maya Digital Studios is now focusing its energy on completing a 3D version of the classic Indian film, “Sholay.” The film is an absolute must-see for Indian audiences and held a box office record for 19 years. Re-releasing the film in 3D is sure to result in another good box office return.

Sara and I got to watch the Maya Digital Studio show reel and although it is the first studio to produce its own feature length animated film, “The Ramayana”, the detail of the animation we were seeing was not quite to the standards of American and Canadian animated productions. While Maya has the technology to do this kind of animation, Indian production companies are still adjusting to the workflow of an animated film. While it would be quite standard to produce a feature length film in 3 months, the animation industry cannot be held to the same kind of deadlines. However, this seems to be an opportunity where a coproduction treaty with Canada can be useful. Increased coproductions with Canada can help streamline the process of producing an animated film, and increase the resources necessary to allow the animators the time required to produce high-standard work. Ketan Mehta is already preparing for what he hopes is the imminent signing of the coproduction treaty. Already doing lots of work with Canada and the United States with 2D – 3D conversion, Ketan is hoping that soon that won’t be the only kind of project they are doing with North America.

Pune, Maharashtra: Regional Cinema and Filmmaking in Bollywood’s Shadow

Through a reference we had met at the workshop in Chennai, Sara and I got in touch with Kranti Kanade, a filmmaker based in Pune. We also got a reference from Manoj Lobo to contact Girish Kulkarni (Pune-52) and we were very excited to have a chance to meet him as well as visit the famed Film and Television Institute of India (FTII), where so many of the filmmakers we had met had gone to school.

We first visited Kranti and had the opportunity to watch his entire body of work including some of his unreleased feature “Gandhi of the Month” starring Harvey Keitel. After Kranti’s thesis film won him a National Award, he wanted to make a feature film. The film was going to be produced by the NFDC, but right before the project was Green-Lit, the first-time filmmaker’s funding program was shut down. Still hungry to make a film but without the money to do it, he went to the last resort he knew of. He submitted two feature film ideas to the Children’s Film Society that were both approved for funding. Kranti then made the first film, “Mahek” and this film was a success. After this, Kranti went to Los Angeles and did a course in Producing. He came back to India but the idea of his second children’s film had evolved. This film became “Gandhi of the Month” and was made with American money although shot exclusively in India. Through Kranti’s experience, we learned that there are other ways of getting your film made if it isn’t Bollywood material or a Children’s film. We also realized that Canada should not be expecting to make coproductions with Bollywood or the other successful industries in India but rather involve itself with regional cinema where money is harder to come by.

Another filmmaking pair based in Pune has also had some success outside of Bollywood. Umesh and Girish Kulkarni (Pune-52, Valu) have written and directed together since Umesh was attending FTII and Girish was acting in his films. Together they have successfully distributed three films in three different ways. The first film was the hardest to get off the ground. In order to raise money for it they had friends and family invest their money with the promise of paying them back. After they made the film, they sold it to a Bollywood distributor and got enough money to pay back their debts. Because of the box-office success of the first film, a Bollywood production studio agreed to work with them on their next film. A private businessman who had decided he was interested in making a Marathi film funded their most recent production. However, Girish has found it quite difficult in all cases to properly distribute and market the films once they are made. While both their first films had distribution and marketing taken care of my the companies that bought the rights, they found that these companies neglected to market their films properly because they were assumed to automatically not do well in the box office. This is because they were Marathi-language films, and the companies would instead focus most of their attention on the Bollywood-Hindi productions. While Umesh and Girish were quite careful with that process, they found they had to be completely involved in the distribution of the film and do most of the work themselves or else it would be neglected. Meanwhile, the issue with private businessmen is that once the film is made the producers usually lose interest in the project and make no effort to distribute it. As a result, Girish says that out of 100 films that get made in the Marathi industry, perhaps only 5 to 10 films will ever be exhibited. This can be quite exhausting for the filmmakers, and as a result Girish and Umesh have had to take a full two years for each of their films to be produced and distributed. Then they find they need a break because it is such an exhausting process. This then results in fewer films being made compared to directors who only have to worry about making the film and then can move onto the next project before it even hits the screen. On the other hand, at least these films are being made and Umesh and Girish have the drive to make them seen.

The next stop for us was to visit Indranil Battacharya at FTII, Pune. Indranil is a film appreciation professor at FTII and he was running a summer film appreciation workshop and everyone was very busy. He started us off by letting us sit in on one of the lectures, and then had a student give us a tour of the campus. That day there was a class on Animation. The lecturer was trying to teach the students about the different forms of animation by showing short films and opening up discussion on why different forms of animation would be effective for different types of stories. We were happy to see that Canada was being well represented onscreen. However, once the discussion opened up, the dominant question was, “How did they do it?” Frame-by-frame animation and the way that film works were explained, but again the question came up after each film. It seemed like the students wanted to learn how to animate instead of learn when and why to use it.

We wondered why this might be, and a few weeks later we realized that these students were our age, yet animation has only become common in India within the last 10-15 years. These students probably did not grow up watching Disney on VHS and seeing the Disney promotional shorts where they show frame-by-frame drawings of “The Lion King”. As far as I know, these films were not available with Hindi subtitles in those days, nor can it be expected that an Indian child would be able to understand the English versions of the film when English is their second-language. However, when I think of animation, it seems I have known how it works my entire life because I had watched the Disney animation videos repeatedly from before the time my brain was fully developed. However, animation has only been used recently in India for telling children’s stories and is not considered by many audiences as a form of adult entertainment.

On FTII’s film program, the tour that we had been given demonstrated that the school has by far the most studio space and in excellent condition compared to WWII and LVPFTI. This is because it was founded in 1960 in the old Prabhat Film Studios, which were left standing as Municipal Heritage Sites. We did not get an in-depth tour of the digital facilities but did have a chance to see the large mixing theatre that students could do their final mixes in. However, it seemed that only space was what FTII had in its favor when competing with WWII. Unfortunately, some of the people with whom we had discussed the school found that the instruction was not with the other schools mainly because in the last few years it has not had the money pay professional filmmaker’s to come teach. It is a government-funded program that takes on batches of 12 students a year. While in the past, it had a great standing as the elite National film school, these days it has been struggling to survive and even tried increasing the number of students per batch.

Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh: Southern Cinema and Fandom

The last area we knew we had to research was Tollywood. At this point, we had heard so much about Southern film and filmmakers as being both a source of new stories and having a successful commercial film industry. In order to learn more about what makes Southern cinema different from the North, we managed to meet with Mohan Krishna (Grahanam), Jayanth Paranjee (Theenmaar), and Daggubatti Suresh Babu (Suresh Productions). All three confirmed the overall impression we had garnered so far, that the main difference is the world in which the story takes place. Mohan Krishna started his film career by attending York University in Canada, and then says it took him ten years of pushing to break into the Tollywood film industry. He says that a big difference is that a lot of Telugu-language films take place in an alternate reality, or at least an enhanced version of the real world and tend to have heroes that are more often middle-lower class. This is in contrast to mainstream Bollywood cinema where glamorization enhances the reality and the stories typically deal with upper-class families. Suresh Babu also speculated another reason for the choice of middle-lower class stories as a result of the inherently lower production budgets. This is all said with the caveat that recently there have been some very successful Northern films that show heroes who come from middle-lower class backgrounds who elevate themselves to an upper-class status through heroic acts or crime.

Jayanth Paranjee has been directing films in Tollywood for many years. When we asked him about the new strain of corporate studios in India he answered that while they have been managing to gain a foothold in the North, they are struggling to integrate themselves with the Southern industries. The reason why is that for as long as filmmaking has been a business in the South, it has mostly functioned on the “feudal” system (previously discussed with Deepti Gupta and Manoj Lobo) where the director has ultimate control and works with a producer who will accommodate their needs. Having attempted to work with a corporate studio before, Jayanth says that there is just too much red-tape making production difficult. The sudden implementation of Western studio practices has not worked for Southern filmmakers, and the industry is so successful on its own there is no need for them to change the way they work.

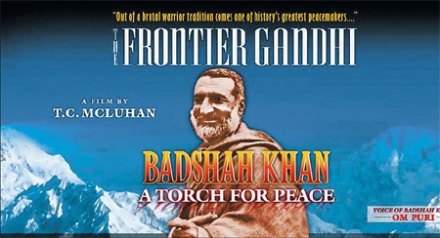

While in Hyderabad, we noticed a bunch of posters and billboards featuring an animated picture of a housefly. The tagline was “The Ultimate Revenge Story”. This was something Sara and I were wondering about, as we weren’t sure if it was promotion for a film since there were no stars on the posters. While chatting with Suresh Babu, we asked about the posters because he had one in his office. It turns out that the film is produced by his company, and is a story about a man who is reincarnated as a fly and finds a way to take revenge on the man who killed him and stole his lover. What we found surprising was that we had been told that audiences didn’t take animation seriously in India because it was seen as a way of telling children’s stories. However, Suresh Productions was taking a chance and telling an adult-themed story where instead of a star playing the hero, there is an animated housefly. It could be that with the release of this film, the general perception of animation in India will start to change. So far the film has done well, reaching a box office total of 17 Crores in its first day worldwide and reached its 50 days in theatres August 24th.

Jayanth wanted to make sure we had the full Indian film experience before we left the country. Up until this point, Sara and I had seen films like “Shanghai” and “Cocktail” in multiplexes. However, we learned that this is not the right environment to get a full grasp of how Indian audiences watch movies and why the films are so different from Western cinema. We managed to book tickets to see the film “Gabbar Singh” which had been playing in theatres for about two months by this point. Unfortunately there were to be no big releases during our last few days in India, but apparently it is something to behold. Stars are idolized in India far beyond the Hollywood star-system, so when a big star has a film release audiences will line up the night before to catch the 11:00 am showing. There are sometimes large cardboard cutouts of the film stars that are bathed with gallons of milk as a blessing, and people perform pujas and bless the movie posters on their way into the cinema. When Sara and I went into the massive single-screen theatre, the theatre was about 1/3 full but for weeks after a film is released it will be sold out at every showing. During the projection of the film, we finally realized the other reasons why the film will release the big item songs before the premiere. Some members of the audience got out of their seats and went in front of the screen and were singing the song and doing the signature dance moves with the film. It was like a live concert. When the hero was first shown the audience cheered and clapped and whistled at the sight of the star. I had wondered why commercial films put so much emphasis on these big moments by using slow-motion walks and freeze-frames. The films need to leave that space the same way a comedian needs to leave space between jokes for the laughter to die down. The long spaces are filled with cheering and whistling. I have to say that the entire way through “Gabbar Singh” I did not feel the length the way I would have had I been watching at home. The biggest influence on Indian cinema is the audience. The audience wants to participate with the film instead of sit back and get lost the way Western audiences do. This is most likely the reason why Western audiences have trouble relating to Indian commercial cinema. While in Western countries we have a similar experience with cult-films like “Rocky Horror Picture Show” the audience participation arises out the film culture that has developed over years. The same can be said for new-releases of films like “The Dark Knight” where despite the film being a new-release, the story of Batman has built enough of a cultural following that the audience feels free to applaud and cheer during the film. So while Western audiences place their fan-energy on stories and fictional characters that have been developed culturally over time, Indian audiences have the same energy but directed toward the stars who have developed their fan-based culture over time.

Chennai: The Music Industry

Stars and music have always been a very important part of Indian cinema. Before a film is released, the marketing of a film revolves predominantly around these elements rather than promoting the story. At the end of Sara and I’s journey, we returned to Chennai for our last week. After being around the country we had made some friends and as a result managed to connect with Devi Sri Prasad, a prolific film music composer and musician at his studio in Chennai. While Devi is only thirty-three years old, he has won many awards for Best Music Director and has worked with films in Telugu, Tamil, and Hindi. We managed to gain some insight on the music-production side of filmmaking. The popular music industry in India is dominated by film music instead of musical groups and bands. As a result, there is a lot of work for musicians in India who want to be involved in film music because are so many films. Typically the songs are written when the script is in its final stages and fully recorded so that the song sequences can be filmed with the stars singing the parts and dancing to the right beat. Sometimes the stars sing the songs themselves, but more often than not a different singer will record every song in the film even if the same character on screen sings them.

Sometimes new song sequences will be added to the film after the principal shooting has been completed. This happens when the filmmakers find that there are holes in the story or that there needs to be a song in between scenes to allow for an emotional shift. However, recently there have been more and more films that don’t have many synchronous song and dance sequences and the music is added once the film is in post-production as is usually done in Western cinema. Despite this, music remains an incredibly important part of films for Indian filmmakers whether they are making new wave, Regional, Bollywood, Tollywood, Kollywood or any other kind of Indian cinema. If the importance of music for Indian cinema was not fully clear for us, we learned that film composers were used to promote the film as much as the stars. While we were in Chennai, we went out one night with Devi Sri Prasad and Tollywood star Charmme Kaur. While Charmme was not recognized so much in Chennai, she would not have been able to go out in public in Hyderabad without being mobbed by fans. We got an idea of how it can be for composers as well when throughout the night Devi was constantly drawing stares and was regularly asked for photos and autographs.

Conclusion: Collaboration with India

With all this fandom, a gross production of 1000 films released a year, and the international status of Indian cinema; one might think that Canada has nothing to offer. The truth is that coproduction is only ever an option when there are two industries that need each-others help to tell a certain story. I don’t see the future of Indian coproduction being more Bollywood films shot in the Rocky Mountains. I also don’t see it as a way for Canadian productions to outsource labor costs to India (Coproduction treaties include clauses to prevent labor imbalances). Bollywood has been and will continue to be very successful on its own within India, but I see coproduction functioning for Bollywood as a way to expand its audience and tell transnational stories. We have all seen the success of Danny Boyle’s “Slumdog Millionaire” but it is a U.K. production. The screenplay is written with a Western sensibility and as a result it resonates more with Western audiences. Perhaps coproductions will allow for a blending of storytelling sensibilities and create new international audiences.

Additionally, the areas ripest for coproduction are the ones that need the most help. Regional cinema like the Marathi industry based in Pune need producers and distributors who aren’t invested in Bollywood to take care of their films. These regional industries also have potential to output transnational stories, explore and create new ways of telling stories through film, and less pressure to conform to the classic formula. Animation is also an area in which Canada excels that India is only beginning to use as a serious form of storytelling. While the film “Eega” may be starting to overcome the assumption that animation is only for children’s stories, Canada can offer increased exposure to the Indian industry by increasing the production of Indian stories told through the animation-medium, as well as a transfer of best-practice to help increase the visual quality of Indian animated films.

Coproduction between Canada and India has the ability to internationally increase awareness of Canadian cinema and filmmakers by expanding its Indian audience. Through coproduction, I see new kinds of stories being told that reflect our current globalized world. Through international collaboration, I see new grammars of filmmaking being forged, and new audiences being made.

Notes:

A very special thanks to all the wonderful people who helped Sara and I on our journey to India. While not all the people we met were mentioned in the main article, everyone was essential to our journey and we really appreciate the time and effort given to us: Meghna Haldar, Jayanti Ram, Jack Silberman, Brigitte Monneau, Nimisha Mukerji, Patricia Gruben, Richard Brownsey, Aysha Iqbal and the student organizers of Imaging Cinema, Atul Tiwari, Sudish Kamath, Mugil Chandran, Shridar Raghavan, Sriram Raghavan, Ravi K. Chandran, Chatura Chattaram, Shilpa Mukerji, Uma Vangal, Mr. K. Hariharan, Gauri Chicliggur, Chaitanya Chinchlikar, Anjum Rajabali, Rashmi Condra, Kranti Kanade, Shakuntala Kanade, Amit Kumar, Izaak Haarhoff, Indranil Bhattacharya, Rohan Sippy, Roopa De Choudary, Garima Mehta, Manisha, Michael Sinden, Deepti Gupta, Manoj Lobo, Nikhil Hegde, Umesh Kulkarni, Girish Kulkarni, Vipin Sharma, Purva Naresh, Anurag Kashyap, Shlok Sharma, Vasan Bala, Guneet Monga, Madhu Mantena, Myleeta Aga, Ketan Mehta, Swati Shetty, Aditi Vasudev, Mohan Krishna, Jayanth Paranjee and family, Salib Gunaam, Prakash Kovalamudi, Daggubatti Suresh Babu, Pritham K Chakravarthy, Our Chennai Hosts, Trisha Krishnan, Devi Sri Prasad, Charmme Kaur.

They have been thoroughly documenting their process with weekly update videos on youtube, as well as their own mini web-series of documentaries featuring interesting people they have met along the way. You can check them out on their youtube channel, and also see their blogs and videos through their website. This will culminate in the gallery installation, but they are also working on other projects.

They have been thoroughly documenting their process with weekly update videos on youtube, as well as their own mini web-series of documentaries featuring interesting people they have met along the way. You can check them out on their youtube channel, and also see their blogs and videos through their website. This will culminate in the gallery installation, but they are also working on other projects. Along this journey, they have also been finding odd jobs like shooting a music video in New York for Marcus Aurelius, an electronic music artist based out of San Diego, and creating a documentary called Coming Home, featuring people who have left Newfoundland and returned home to their community for various reasons. On top of all this, they are also writing fictional feature film scripts and experimental shorts to be executed when they return to Vancouver in 2014.

Along this journey, they have also been finding odd jobs like shooting a music video in New York for Marcus Aurelius, an electronic music artist based out of San Diego, and creating a documentary called Coming Home, featuring people who have left Newfoundland and returned home to their community for various reasons. On top of all this, they are also writing fictional feature film scripts and experimental shorts to be executed when they return to Vancouver in 2014.